Writing for the Gardan

A Population of One

By TaraMarie Perri

Artists, makers, writers, naturalists, and contemplatives nurture harmonious relationships with solitude. Rituals and practices give definition and form to time spent along with canvas, kiln, or pen. And yet an unexpected abundance of solitary time could uproot the most well-honed creative environment.

Solitude as a state of being elicits a variety of responses: fear, avoidance, yearning, and romanticizing. Solitary time is rich fuel for the creative process and sometimes the loneliest place on earth. A profound tension arises in our solitude. We witness the vastness of our inner world and find humility in our relatively small presence on the planet.

Stillness, like solitude, may be startling at first, though it is commonplace to hear complaints of “busy” and “no downtime” and “just wanting time for myself” in response to the constant movements and structures of modern living. Perhaps these habits of mind become deafening when we sit alone or in the absence of our usual distractions. Perhaps the simplicity we crave feels uncomfortable when we try it on. Our nervous system wiring has been trained to look for a schedule and the next dose of alerts delivered by our devices. Doing is familiar; being is elusive.

The human desire to connect to move and commune with others is natural. However, an aversion to being alone with still simplicity is one to patiently investigate. The escalating pace of our world is ultimately unsustainable; taking a pause gives us the rare opportunity to practice trusting the necessity of our solitary time again.

What if the current daily experience - or “slow living” - were a fresh mode of creative practice and contemplation? What if home were a mountain retreat? And solitude were studio? And stillness the master teacher?

No matter what our vocation, every being is entitled to a meaningful life. Contemplative arts take many forms and creative forces have an organic way of forging new pathways. Experiment with living slowly and simply. Cook, read, walk, sit, listen, breathe, rest, reflect, remember, daydream. Use your senses. Think less. Feel more.

Pico Iyer writes in The Art of Stillness, “Movement makes richest sense when set within the frame of stillness.” When we become deeply still our natural rhythms come forward. Remain open to a variety of outcomes.

We do less. We do only what needs to be done. We slow down. We get out of our own way while new ways of making art find an opening to emerge. We let go of products and goals. We welcome process and path. We discover we already have everything we need. We forge deeper relationships with nature and others. We make friends with who - and where - we are.

Iyer further offers, “The idea behind Nowhere - choosing to sit still long enough to turn inward - is at heart a simple one. It’s the perspective we choose - not the place we visit - that ultimately tells us where we stand.”

Nowhere. Population of one. Pitstop of destination. Where solitude is fertile ground.

Reemerging

By TaraMarie Perri

One recent snowy February morning, I gently wept in front of Willem Claesz Heda’s Still Life with Oysters, a Silver Tazza, and Glassware, a painting in the Met’s current Dutch Masterpieces exhibit. Dutch painters have always been lauded for their mastery of light, reflection, detail, and realism. First glimpsed with the click of a slide projector in a stuffy classroom as an art history major, I made many efforts to view these works in person whenever possible.

What was it about this particular painting and viewing that brought me to tears? The scene nearly knocked me to my knees as I exhaled my share of the collectively-held breath of sensory deprivation and relative solitude we experienced over the last year. I could smell the astringency of the partially peeled and tactile citrine-yellow lemon. My hand naturally curled into a “C” shape as if to upright the overturned silver tazza on the table. The reflective oyster flesh, knife, and drinking glass against the somber background unified a boundless sea and the intimate setting of a quiet meal. No doubt, Heda’s painting indicates a solitary scene. That winter morning, however, it transformed into an offering for anytone coming to his table, seeking nourishment or company.

One recent sunny March morning, I climbed out onto my urban outdoor space to get a pot out of the trunk where I store supplies over the winter. Last fall I tucked five hyacinth bulbs, a grouping I enjoyed in full bloom last spring, into a large pot, after dutifully restoring their lifeforce in a cool dark place over the summer and a single month in the refrigerator next to the pickle and olives. When I lifted the trunk lid, five vibrant green upshoots were growing, ready and willing to thrive on the outside and carrying a message for me. I recalled that a full year prior, two weeks after New York shut down, I was lured by their velvety purple scent to a farmer’s table at my local market alongside their fellow early spring ambassadors of crocuses and daffodils. Masks and social distancing were new concepts then and navigating the market was awkward. Beyond their intoxicating smell, I brought the hyacinths home with me for their graceful company. I recognize now that the ways I tended to the bulbs over the year were not so different from how I had to tend to myself. Affirmation of our own human life cycles can often be found alongside nature. Dormancy is often overlooked yet necessary phase within a life cycle. Growth requires a period of time for storing nutrients, gaining strength, and waiting for the right conditions.

It seemed unimaginable we would experience the cycle of an entire year living primarily as indoor creatures when we began sheltering in place in March 2020. At the table of a Dutch master and within a hyacinth’s life cycle of one year, the experience of my own year has gained new perspective.

As winter gives way to spring each year, we are supported in all our usual intentions for renewal. With spring’s arrival, nature calls and we thrive more easily outdoors. We can get back in touch with the vital experience of what it means to be alive and living.

As winter gives way to spring this year, we are supported in revealing new and tender - perhaps simpler - ways of being that were seeded in response to a year of challenges. Every spring, and especially this one, we are invited to re-emerge with lifeforce and tried and true grace.

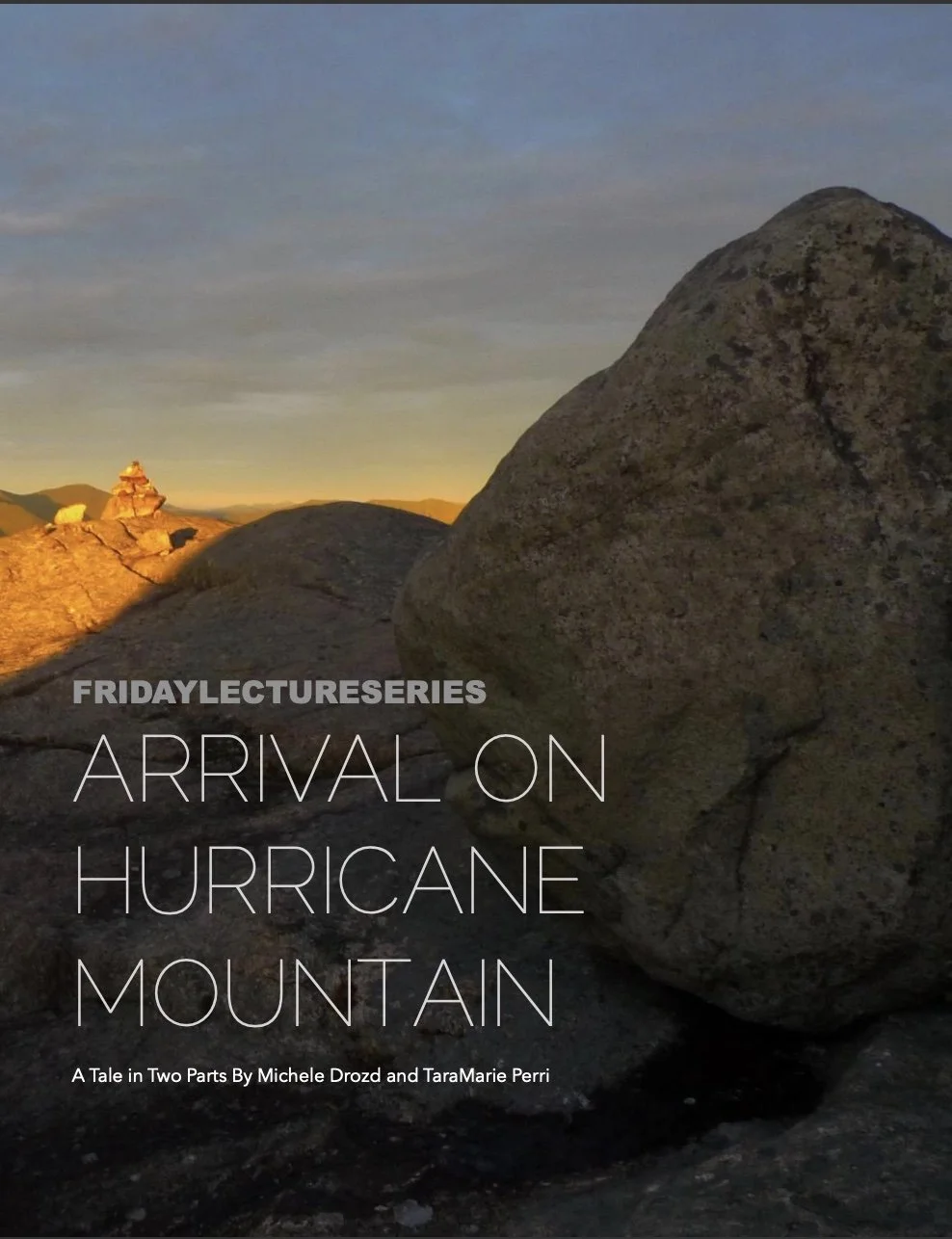

Arrival on Hurricane Mountain, How We Will Arrive: Part Two

By TaraMarie Perri

Humans have been going up into the mountains since the beginning of time. Wise people, hermits, seekers, artists, farmers, and adventurers alike have taken the trek. The allure of solitude, peaceful abiding in nature, expanding views, and discovery speak to the heart of their quests, often fueled by an intention to answer life's greatest mysteries. Many ancient cultures - Egyptians, Incas, Mayans, Romans, Greeks, Native American Indians - have wise ones: the seers who held the secrets to the well-being and harmony of a place and a people. The wise ones often have mountain stories or anecdotes of going up into the clouds. Upper worlds, heavens, sky mind, birds-eye view are all aspirant metaphors for the place above us associated with attaining peace or wisdom or higher intelligence.

The ancient culture of India celebrates the rishis. The term rishi derives from the Sanskrit root which means “to see”. The rishis were a soulful tribe, of sages and poets, who had mastered the highest forms of spiritual practices through meditation. It is written that they also possessed acute control of their nervous systems by training and strengthening their senses to unlock deeper perceptions. Hence they cultivated a keen understanding of nature and the greater universe. Over many generations the rishi-scientists ascended into the laboratory of the Himalayan mountains. From above, the rishis studied humans, oceans, sun, moon, planets, stars, animals, herbs, plants, elemental properties, and seasonal cycles. Their observations over time compiled an understanding of the dynamic relationships between nature and the human body, what causes disease, and the potential for the elements and cycles of the natural world to heal us.

The stories, parables, and tales that survive throughout generations and translate across lands and cultures are few. The rishis are part of an ongoing history of wise ones, intentional communities, and fertile lands. This history is an invitation for the moment and a harmonizing principle for our future.

Today we are still contemplating as we experience new challenges of human living as part of the natural world. The tradition of going into nature for a hermitic or contemplative life is a choice extended to everyone. The upward trek now serves as rite of passage. The mountaintop is a peaceful refuge for residence and communing alone or with others in nature. The practices of awakening our senses, eating seasonally, making, and working on the land are reappearing as revolution and remedy to the challenges of technology and contemporary life.

What if these practices are also a reconnection to the ancient human intelligence already living deep within our cells? Our nature is to quest and question, and the mountains continue to draw us back home.